Poetry

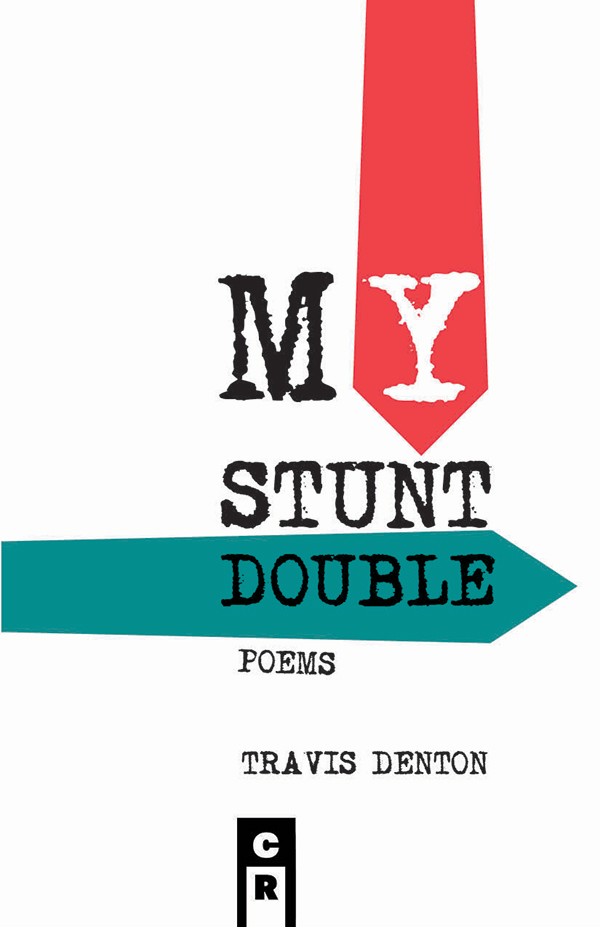

My Stunt Double

by Travis Denton

C&R Press

92 Pages

ISBN 978-1-936196-90-6

by Micah Zevin

Are we Gods/gods and comic book heroes or are we merely playing them on the page and in movies, only imagining our real life prowess? Should we be fascinated and full of ecstatic joy about what we see and encounter on our journey? Are we our bodies? Who and what is a man? Does he have doppelgangers or merely wish that he did so that he could play many parts? In Travis Denton’s My Stunt Double, descriptive lush sometimes-humorous poems are like a painters canvas that has very little use for lingering too long in darkness, melancholy and apocalypse. All of his characters, but especially the male ones, are fascinated by all sites and sounds real and imagined.

“What Beauty Gives Us,” sets the tone of inquisitiveness whether the narrative is about life or death: “A head, I think of its dying,/Of all their dyings—how they could have died/One by one, generations— fathers, sons,/Idiots and bastards—until the very last/Stands looking out on a greeny-blue dot/Out of reach, yet he reaches, grabs for it,.” The speaker is on a quest of discovery and understanding, and whether or not he ultimately succeeds, he keeps striving. In the title poem, “My Stunt Double,” we are transported to a cinematic world that reminds one of scenes from Robert Altman or Coen brother’s movies:

In my rock-n-roll days, my stunt double

Was called in to sweet talk girls

After a show. I watched

The tangle of hair and hands knit

Into a good story. My job was to blast

The plaster from the art,

While the smell of my own breath and sweat

Made me sick, balancing on two feet

Of shifting sand as tablesful of work

Stared me down.

Denton plays with the notion of knowing ones self and then conjures attributes and actions onto this other version of an actual self who is more successful than its double, who is perpetually in trouble but in certain situations is helpful.

“What the Satellites Saw” is a double sonnet that utilizes word play, humor, classic mythological characters and even a few modern references to comment on dark subject matters. “And the storm surge in all of us//In all its holy ghostiness pronounces us alive/As we Google what to make with the hail/The storm left—ice cream? Or if it’s enough/We’ll pack our wounds with it.” Even when the apocalypse is mentioned at the end it is delivered with a wink like comedic song lyrics. In the “The Body Next Door,” a husband and wife morbidly wonder what has happened to their elderly neighbor inventing theoretical scenarios to explain it: “My wife suspects he’s in there,/In the threshold to the kitchen, arms stretched/Out for the phone inches from his fingers,/Face and eyes caught in that look of wonder/That only the dead have perfected.” As they decide what action to take, the husband starts to make up a narrative of his own: “I’ve begun to imagine him, not facedown on checkered linoleum,/But having wandered off toward the woods/One evening, losing a slipper on a tree stump,/Limping into that forest, his ex-wives asleep/Elsewhere.” The characters inhabiting these and other poems in this collection are consistently curious regarding all aspects of human existence whether they are light, dark or somewhere in between.

The work is remarkable in that a majority of its stories takes place in the mind whether the dreams and images are conscious or unconscious. In “ The Rooms We’ve Never Left or Entered” figures in conversation speak to what they wish they had seen: “We watch a squirrel on the landing, a workman/Filching a beer from his fridge. My friend laughs in absentia, and later/We turn on the mic and take turns speaking into that space, “Mayday, mayday,” filling it like a megaphone that distorts.” There is music in Denton’s lists and descriptions. “Post Apocalypse” even brings wonder although death, disease and bombs that once robbed him of sleep is omnipresent: “Now his chest was paper-mache,/His back, a canvas. In years to come, He’d yellow like newsprint,/Crack spot with mold,” and “his lawn/Like gift wrap, his street—cardboard, and the sky/Endless reams of high cotton—planes twisting,”. Everything is valued in this world even if it is a world that seems doomed or that must recover from its erosion.

Rounding out this collection and sprinkled throughout are a series I will call the ‘man’ poems. Several of these pseudo-memoirs are from the point of view of an anonymous man recounting his life make-believe or real. “Man one night sitting out with a drink,” is a lyrical soundtrack homage to stereotypical male hero figures in the movies and their romantic encounters, specifically the Magnificent Seven: “They lay there/In her twin bed, and he did not think/of one back South who’d leave all/She thought he owned on the porch one day/In years to come, leave him to a friends couch.” In “Man once thought to himself,” there is an beautiful recounting of a day in the life of a ‘normal’ man in all his existential frustrations: “The street was silent, and his wife/Was not snoring her usual snore. It was quiet/And he cursed the silence,/Wished he could take it up in his hands,/Wrap his hands around that soft body. He’d pitch that shadow from the moving train/Of his bed and be thought hero by all.” There is a deluge of sensory reactions by the characters in this poem and a focus on the body and its role in his life as well as an ominous violence and anger possibly beneath the surface. These morbid and now, spiritual themes, come full circle in “Man, one day, started believing”: “Sometimes he’d want tea, and he’d walk to the kitchen/And there was his cup steaming on the counter./What a life, he thought, to be haunted by a butler God/Or housewife God who brought his slippers/To his bedside during the night.” This poem in the ‘man’ series is one where he reckons with his journey from belief to non-belief and comes back again.

At the conclusion of most of these stories, the characters learn something about themselves and seem better for it, not just that the darkness is inescapable. The intoxicating and inventive music, stories and characters that inhabit Travis Denton’s My Stunt Double are treated with sensitivity towards the body, the mind and our aging with a joy and curiosity that insists on honesty in all of its specific and poignant details.

Fuel for Love by Jeffrey Cyphers Wright

Alexis Rhone Fancher’s Erotic: New and Selected Poems

Chasing Homer by László Krasznahorkai

Eight Perfect Murders by Peter Swanson

The Death of Sitting Bear by N. Scott Momaday

WHILE YOU WERE GONE BY SYBIL BAKER

MY STUNT DOUBLE BY TRAVIS DENTON

Made by Mary by Laura Catherine Brown

THE RAVENMASTER: My Life with the Ravens at the Tower of London

Children of the New World By Alexander Weinstein

Canons by Consensus by Joseph Csicsila

And Then by Donald Breckenridge

Magic City Gospel by Ashley M. Jones

One with the Tiger by Steven Church

The King of White Collar Boxing by David Lawrence

They Were Coming for Him by Berta Vias-Mahou

Verse for the Averse: a Review of Ben Lerner’s The Hatred of Poetry

Ghost/ Landscape by Kristina Marie Darling and John Gallaher

Enchantment Lake by Margi Preus

Diaboliques by Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly

Core of the Sun by Johanna Sinisalo

Maze of Blood by Marly Youmans

Tender the Maker by Christina Hutchkins

Conjuror by Holly Sullivan McClure

Someone's Trying To Find You by Marc Augé

The Four Corners of Palermo by Giuseppe Di Piazza

Now You Have Many Legs to Stand On by Ashley-Elizabeth Best

The Darling by Lorraine M. López

How To Be Drawn by Terrance Hayes

Watershed Days: Adventures (A Little Thorny and Familiar) in the Home Range by Thorpe Moeckel

Demigods on Speedway by Aurelie Sheehan

Wandering Time by Luis Alberto Urrea

Teaching a Man to Unstick His Tail by Ralph Hamilton

Domenica Martinello: The Abject in the Interzones

Control Bird Alt Delete by Alexandria Peary

Twelve Clocks by Julie Sophia Paegle

Love You To a Pulp by C.S. DeWildt

Even Though I Don’t Miss You by Chelsea Martin

Revising The Storm by Geffrey Davis

Midnight in Siberia by David Greene

Strings Attached by Diane Decillis

Down from the Mountaintop: From Belief to Belonging by Joshua Dolezal

The New Testament by Jericho Brown

You Don't Know Me by James Nolan

Phoning Home: Essays by Jacob M. Appel

Words We Might One Day Say by Holly Karapetkova

The Americans by David Roderick

Put Your Hands In by Chris Hosea

I Think I Am in Friends-Love With You by Yumi Sakugawa

box of blue horses by Lisa Graley

Review of Hilary Plum’s They Dragged Them Through the Streets

The Sleep of Reason by Morri Creech

The Hush before the Animals Attack by Carol Matos

Regina Derieva, In Memoriam by Frederick Smock

Review of The House Began to Pitch by Kelly Whiddon

Hill William by Scott McClanahan

The Bounteous World by Frederick Smock

Review of The Tide King by Jen Michalski

Going Down by Chris Campanioni

Review of Empire in the Shade of a Grass Blade by Rob Cook

Review of The Day Judge Spencer Learned the Power of Metaphor

Review of The Figure of a Man Being Swallowed by a Fish

Review of Life Cycle Poems by Dena Rash Guzman

Review of Saint X by Kirk Nesset