January 23, 2015

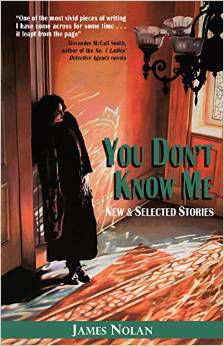

You Don't Know Me

by James Nolan

University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press

$20 Paperback

296 pp.

ISBN: 9781935754343

by Beth Gilstrap

In his latest collection YOU DON’T KNOW ME author James Nolan, (Higher Ground 2011) world-building is as complex and intricate as any found in popular fantasy fiction, but he’s working with a city that’s already carved into this nation’s consciousness. Everyone has some idea of New Orleans whether they’ve visited or only heard its tales of joy and woe. A place as storied as New Orleans, however, takes on a slippery mythic quality and unless someone has this city in their blood and bones the way James Nolan does as a fifth-generation native, it becomes nearly impossible to capture. One weekend trip during Carnival is not going to do it. Images of people stranded on rooftops during Katrina is a flicker of this city –a flash in its gigantic history. Thinking back on other portrayals, they seem smudged in pencil by comparison. Nolan writes of his city with fire, showing us a blend of misfits and old money, of black and Hispanic, of an unlikely elderly terrorist, drag queens, white and creole, and each nook and cranny of the city from the French Quarter to the suburbs in the dead of winter, after the storm, and the mosquito-drenched wet summer. This is experience and knowledge and nuance that only comes with deep roots such as Nolan’s. I have that myself in North Carolina and to have roots like that means you walk with ghosts –ghosts of all you know of the place and all your people knew going way back.

YOU DON’T KNOW ME is divided into two sections. The first ten stories are new and the second are from his earlier collection PERPETUAL CARE: STORIES (2008). The first section starts with “Reconcile” -a post-Katrina story in which we bear witness to a group of colorful characters trying to make the best of life in their deteriorating French Quarter apartment building. I normally don’t care for stories with pets in them since they inevitable shuffle off this mortal coil, but this one has so much love and loss hanging in the balance that I can forgive the transgression. After all, the dead in New Orleans after the storm were human and non-human alike. Nolan’s characterization of these neighbors is darkly comical and this sensibility is what keeps the reader turning pages. Sherene says of her neighbor:

“When Zola’s mam was still lucid, she swore up and down that studying medieval art history at Tulane University was where her daughter picked up ‘those funny notions’ and wound up a spinster in the trampy French Quarter working at no-account jobs. But Zola still swears by Texas and the President. Claims she has crude pulsing through her veins. Now that I’ve seen her without makeup, I believe it.” (7)

If a character description such as this doesn’t draw you in, I don’t know what would. This world is volatile and quirky and everything I want in a story. “Reconcile” highlights the morbid humor of the aftermath of the storm when the narrator mentions clinking glasses Mardi Gras party guests in their hysterical costumes. The narrator says, “Never before have I seen anyone drink a pina colada and eat a bowl of gumbo while dressed as a moldy refrigerator” (14). Though things don’t end well for Boom Boom the dog, we are left with a sense of hope and resilience.

“Hard Freeze” is the story of Emile Jackson, a famous concert pianist, looking for his New Orleans roots though his search for belonging is more complicated than he expects. As half African-American, half French, growing up in France, he always felt like an outsider despite the fact that his mother raised him to be “one hundred per cent French.” He did not look the part. After the storm when they invited him to play a benefit concert, he expected upon arrival in New Orleans, “with its French history and African bloodlines, where he long dreamed he would melt in like chocolate, he felt particularly foreign.” (20). Like the city itself, Emile is not entirely American, but not quite European, either.

Other stories in this section include: “Under the House” which explores the paths of rebellion from both child and parent; “Mary Sorrows,” the story of a pregnant Hispanic teenager raised in New Orleans who learns that sometimes anguish and sorrow and loneliness lead to strength; “The Whole Shebang” sees the collision between a divorcee with too much furniture (in true southern gothic fashion, some of it winds up in the yard) and a philosophy professor whose career has stalled; “The List” tackles the absurdity of life in the story of Nick Fazio’s fortieth high school reunion; and“Latins on the Loose” peeks into the lonely life of one man who’s tired of the crackpot locals and tourists he picks up in bars of the French Quarter.

My favorite moment of the entire collection comes in the lovely and strange “The Empty Throne.” Wally Wiggins has been a disappointment to his wealthy socialite parents because, in their world, the only way to make them proud was “becoming an Episcopal priest, making several million dollars, marrying a debutante, or reigning as the king of a Mardi Gras parade” (100). When Wally is elected the “King of Mirth,” he had no idea it would “lead to the most humiliating night of his life.” After fighting with his cheating boyfriend and drinking all day on an empty stomach, he winds up abandoning the float for a necessary bathroom stop at Dunkin Donuts, but it is the tender moment he shares with the woman closing the shop that strikes me as the pinnacle moment of the collection:

“Want to dance?” he asked.

“With you?” Evelyn asked.

“Why not? It’s Carnival.”

He wrapped an arm around her waist, and she snuggled close to him.

“Don’t be getting any ideas,” he said.

“Oh honey, youre just like my sissy brother. I know you go to another church.”

“Why, what you got against Episcopalians?”

While the red lights of a crash truck flashed outside, announcing the tail end of the Krewe of Mirth, Wally and Evelyn slow-danced to the smoldering torch song along the slippery floor in front of the illuminated donut cases, watery eyes closed tight as if dancing alone with lost dreams” (111).

You don’t always connect with blood relatives or with those you think you should. One of the most fascinating facts of this life is how, sometimes, your moments of enlightenment and tenderness come wrapped in the clothing of absurdity, loss, humiliation, and in the company of strangers. This story and the collection as a whole are brilliant illustrations of this truth.

The last two stories of Section I include “Abide With Me,” the sad story of people who prey on the sick and lonely –a gut-wrenching tale of warning that yes, indeed we are all alone and when it comes down to it, we will take what companionship we must and “Overpass” –the unlikely tale of an elderly would be terrorist who is so outdone with “progress” that he plans to blow it up to return his neighborhood to its former splendor.

Section II includes stories previously published, but if like me, you missed them in Perpetual Care, you will be grateful they are reprinted here. These stories are thematically linked by one of the core principles of the southern gothic tradition –decay. “Why Isn’t Everything Where It Used to Be?” follows Boubou Glapion (every character name in the collection is this good) who, because of her dementia, winds up back in the French Quarter that is far different from what she’s expecting: “The farther she rode along the oak-shaded avenue, the further back she was carried, as if the gnarled branches of live oaks were passing her, like tired old nurses, from one pair of rocking arms to another, back to her source” (151).

“Perpetual Care” continues the dark comedic threads with the story of a young suicide victim who has been enclosed in the family tomb (thanks to his hysterical girlfriend) with a radio tuned to a local jazz station.

“The Jew Who Founded Memphis” stays in the cemetery looks at another dysfunctional family, but this time the dutiful son helps his mother restore and clean the angel statue in their family plot to find himself more touched by the experience than he expects.

“La Vie En Rose Construction Company” returns to the French Quarter and a rotting apartment building. Derwood Weems realizes his codependent relationship with his hometown upon moving back to New Orleans:

“Derwood always knew New Orleans would be his undoing...The creative possibilities here seemed endless./

And so did the destructive” (213).

As a southerner myself, this love/hate relationship with the place you were born to, this simultaneous drive to go and to stay, is one I know well and seems to be universal in the region.

Other stories in the second half of the book include: “Open Mike” the story of how poetry destroyed one young woman visiting New Orleans; “All Spiders, No Flies” is a bit of a tragic love song for the Quarter; “The Night After Christmas” shows a disconnected family in their final moment of happiness together; and “Lucille Leblanc’s Last Stand” is southern gothic at its finest and reminiscent of Faulkner with three aging sisters and their long time house keeper becoming more and more reclusive.

“What Floats,” the final story of the collection, is perhaps the epitome of a post Katrina story. It is elegant in its execution with sentences like silk and the enveloping sadness over the irreversible loss will leave any reader with a heart reeling. A young boy grapples with what death means when his mother dies, asking, “Was a star the end of forever?...I needed to wait til Mother got to the end of forever and came back. I hoped it didn’t last past the weekend” (213). Years later after he’s grown up and lived a live away from New Orleans, he returns to his former home and finds that grieving for a city and a mother are striking in their similarities.

YOU DON’T KNOW ME looks at us at or most vulnerable moments, the moments of absolute loss of faith, of self, of love, of home, and finds the glimmer of hope in the knowledge that we all disappoint others and ourselves and yes, we are capable of despicable acts, but we are also capable of connecting to each other through this vulnerability. This is what it means to really see and be seen –when makeup’s worn off, when the city’s in ruins, when you find yourself stripped of your pride, that’s where visibility happens. If I could slow dance with these stories in Dunkin Donuts while drunk and in the arms of a stranger, I would.

Fuel for Love by Jeffrey Cyphers Wright

Alexis Rhone Fancher’s Erotic: New and Selected Poems

Chasing Homer by László Krasznahorkai

Eight Perfect Murders by Peter Swanson

The Death of Sitting Bear by N. Scott Momaday

MY STUNT DOUBLE BY TRAVIS DENTON

Made by Mary by Laura Catherine Brown

THE RAVENMASTER: My Life with the Ravens at the Tower of London

Children of the New World By Alexander Weinstein

Canons by Consensus by Joseph Csicsila

And Then by Donald Breckenridge

Magic City Gospel by Ashley M. Jones

One with the Tiger by Steven Church

The King of White Collar Boxing by David Lawrence

They Were Coming for Him by Berta Vias-Mahou

Verse for the Averse: a Review of Ben Lerner’s The Hatred of Poetry

Ghost/ Landscape by Kristina Marie Darling and John Gallaher

Enchantment Lake by Margi Preus

Diaboliques by Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly

Core of the Sun by Johanna Sinisalo

Maze of Blood by Marly Youmans

Tender the Maker by Christina Hutchkins

Conjuror by Holly Sullivan McClure

Someone's Trying To Find You by Marc Augé

The Four Corners of Palermo by Giuseppe Di Piazza

Now You Have Many Legs to Stand On by Ashley-Elizabeth Best

The Darling by Lorraine M. López

How To Be Drawn by Terrance Hayes

Watershed Days: Adventures (A Little Thorny and Familiar) in the Home Range by Thorpe Moeckel

Demigods on Speedway by Aurelie Sheehan

Wandering Time by Luis Alberto Urrea

Teaching a Man to Unstick His Tail by Ralph Hamilton

Domenica Martinello: The Abject in the Interzones

Control Bird Alt Delete by Alexandria Peary

Twelve Clocks by Julie Sophia Paegle

Love You To a Pulp by C.S. DeWildt

Even Though I Don’t Miss You by Chelsea Martin

Revising The Storm by Geffrey Davis

Nature's Confession by J.L. Morin

Midnight in Siberia by David Greene

Strings Attached by Diane Decillis

Down from the Mountaintop: From Belief to Belonging by Joshua Dolezal

The New Testament by Jericho Brown

Phoning Home: Essays by Jacob M. Appel

Words We Might One Day Say by Holly Karapetkova

The Americans by David Roderick

Put Your Hands In by Chris Hosea

I Think I Am in Friends-Love With You by Yumi Sakugawa

box of blue horses by Lisa Graley

Review of Hilary Plum’s They Dragged Them Through the Streets

The Sleep of Reason by Morri Creech

The Hush before the Animals Attack by Carol Matos

Regina Derieva, In Memoriam by Frederick Smock

Review of The House Began to Pitch by Kelly Whiddon

Hill William by Scott McClanahan

The Bounteous World by Frederick Smock

Review of The Tide King by Jen Michalski

Going Down by Chris Campanioni

Review of Empire in the Shade of a Grass Blade by Rob Cook

Review of The Day Judge Spencer Learned the Power of Metaphor

American Neolithic by Terence Hawkins

Review of The Figure of a Man Being Swallowed by a Fish

Review of Life Cycle Poems by Dena Rash Guzman

Review of Saint X by Kirk Nesset