March 18, 2016

A Conversation with Esther Naor

Interviewed by Heather Zises

Tel-Aviv based artist Esther Naor discusses the creative process behind her solo show Aftermath (on view at Stux + Haller Gallery from February 24th to March 26, 2016) and how it addresses reverberating themes such as immigration, pain, terror, and the current global Refugee Crisis.

Esther Naor, Untitled 6, 2016, dye sublimation on Chromaluxe metal panel

HZ. Your art explores emotionally charged, transitory themes such as migration, boundaries, cultural displacement and nostalgia. Having come from a complex history and cultural heritage yourself—an Iraqi Jew whose parents immigrated to Israel in the early days of its statehood—how much of your personal history informs the work you make today?

EN: Much of my work takes personal issues as a point of departure. A few series, like "My Worry Beads", "Tigris River", "Any Minute Something Can Happen", and more, were born concretely from memories and stories of my parents. My interest in identity and culture arose from this personal history and influenced my work since the very beginning. And, of course, as an Israeli who lives in a constant tension, in a reality of recurring terror events, the November attack in Paris triggered the current series of photographs in which I connected two concerns: the service of young Israelis in the army and the fear of the next terror attack, which can hit anytime, anywhere, through images that I took in an Israeli recruitment base, and the image of a thermal blanket, which kind of became a symbol of the recent attacks and waves of refugees in Europe.

HZ. How do you begin a work: with a concept or with an image, or perhaps both?

EN: I don't see myself as a conceptual artist; I'm more emotional and spontaneous. I do collect images in which I find interest and some of these may wait years in my drawer before I use them. But that’s not always the case. There are groups of works, such as those I created for the "Side Effects" project in 2012, that were born after I had a general idea in mind (in this case the body's betrayal and the confrontation with the healing process).

Esther Naor, Untitled 1, 2016, dye sublimation on Chromaluxe metal panel

HZ. You often incorporate a range of unusual media (casts of human heads, syringes, readymade stretchers) as part of your sculptures and installations. In your opinion, what is the most unorthodox material you have ever used in an art piece?

EN: The most unorthodox material I have ever used is also the first material I used to create my early sculptures and installations: cooked rice. For quite a long time, I was kind of obsessed by this organic and treacherous material, as in that same history and cultural background mentioned above, rice was a basic food, and it was (and still is) linked in my consciousness with the warmth, love and security of my home and childhood.

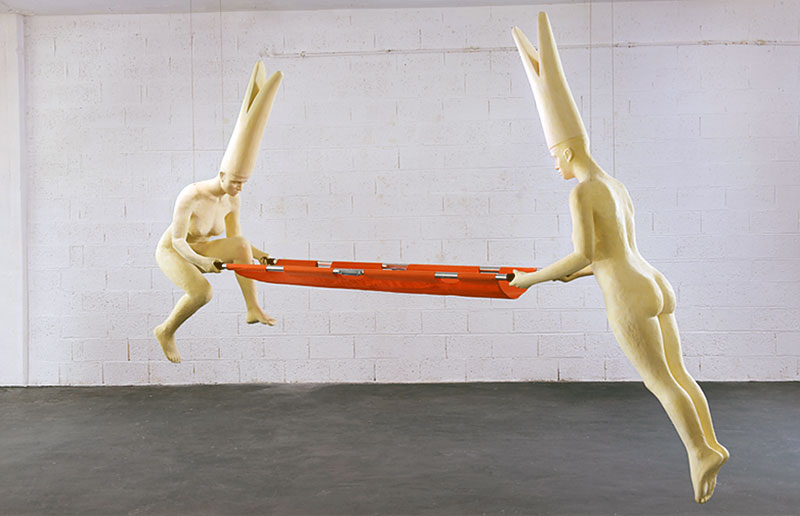

HZ. Many of your subjects appear to be floating or suspended, as if trapped in an uneasy sense of place. Additionally, their lack of context—stark backgrounds, close cropped shots—creates the illusion of timelessness. What (if any) message do you wish to convey to the viewer through these transitory vignettes? EN: Timelessness is relevant here, but it's mostly a way of distilling moments, ideas, images, and emotions – without connecting them to concrete situations and contexts. Although there are concrete roots and sources to many images and situations that I create, I like to leave the final installation open as much as I can. When all the answers are there, I find the result obviously less interesting. HZ. The number three is a recurring theme throughout your work. Most recently, your upcoming show “Aftermath” completes a trilogy of recent exhibitions (Side Effects, 2012 and A Sudden Dark Breeze over My Uncovered Skin, 2015). Why is this number of great significance to you? EN: It's interesting, I'm not sure I was aware of that. I guess I see things as more complete as triads, more valid, maybe, in the sense that conflicts may in many cases be solved with the intervention of a third party. HZ. Aftermath is a somber exhibition that addresses the challenge of living in a time of crisis. Quite fittingly, the subjects in your new photo series seem charged with a religious bent: eyes are closed, heads are tilted upward, and arms appear folded into holy poses. That said, do you think faith and prayer has gained currency in today’s society? EN: I am not a religious person, and didn't mean to charge these images with a religious sensation. True, times of crisis have given birth to religious feelings across history, and even turned people totally towards religion, but what I had in mind was rather despair and helplessness. While I was sorting and selecting the images for this series, I could see here and there the bent that you're mentioning, I guess that strong and true emotions may be expressed in similar ways, even in contradictory situations. That's why the context is so important and that's also why I try to isolate the expressions and let the viewer relate to them in his own way. HZ. Your new photo series depicts two layers of images (people in distress who are embracing and emergency thermal blankets) that are superimposed onto aluminum panels. The combination of textures and patterns creates a chilling trompe l’oeil effect of translucent aging skin that has been stretched across the surface of each picture plane. Did you have a clear vision for how this series would turn out, or was the creative process more organic? EN: The act of superimposing the image of the blanket over the one of the people was itself a kind of embracing, an act of covering and defending. While checking the blanket qualities, I realized that it becomes transparent on a close look and I imagined what the world looks like to a person who is covered with this blanket. I decided then to use it as a kind of semi-transparent curtain separating the viewer (in the role of a covered person) from the figures in the underlying image. In the process of photographing/scanning the thermal blanket, I could choose between having it stretched or keeping its natural folding marks and wrinkles, so I intuitively chose the latter state. Only after superimposing the two images did I have the surprise of discovering the dramatic effect that the wrinkles had on the people's faces and I decided to use this, of course, playing with the extent of transparency to get the results I was interested in. HZ. In your life-scale sculpture Dark Clouds over the Valley, you reinterpret a figure from Goya’s allegorical painting Witches Flight, 1797-98, by shrouding a thermal blanket over a man’s head. What drew you to this particular figure over any of the others in the painting? EN: Well, in the previous exhibition of 2015 mentioned above, I made use of the three flying witches, transforming them into life-scale sculptures: three women engaged in acts of rescue instead of the horrifying act of devouring their victim in Goya's painting. The fleeing man in the lower part of the painting drew my attention as a survivor, and I made allusion to him as I was performing a ceremony for my video work "Three Days under the Pillow", shown also in that same exhibition. In the current exhibition, my main interest was to look at things from the point of view of the individual victim. While looking at the news showing the waves of refugees arriving to Europe, and more so while looking at the victims and survivors of the terror attack in Paris, I empathized deeply with their helpless state of sorrow and trauma. The thermal blanket, present at all these news reports, draped over those poor people, caught my eye and gave birth to the idea of completing the move I have made with Goya's painting by creating another life-scale sculpture based on Goya's character but using a ready-made thermal blanket instead of the original white cloth. HZ. Let’s talk about your interest in witches, the supernatural and magic! Do you look to these concepts as a form of escapism from today’s political and social unrest, or perhaps something else? EN: These concepts – no less than religion - have accompanied the human society since the dawn of history, as ways of dealing with reality at large, with the unbearable arbitrariness and finiteness of life. My personal interest in these concepts arises from social and cultural reasons. As a child, I witnessed and participated in family and friends gatherings in my parents and grandparents houses, where the women were practicing ceremonial acts of telling the future or removing the "evil eye" from "misfortunate" persons, but I perceived these gatherings as feminine acts of mutual support and warmth, as they really were actually, since this was not done with the seriousness of some New Age practitioners nowadays, rather as a social activity or kind of entertainment. But I think I also have always been attracted by images and objects associated with witches, such as the long and pointed hat, the long animal-like nails, the stick, etc., and these are to be found in several of my works as you have noticed. HZ. Finally, do you consider witches to be feminists? EN: The witch represents for me a strong, independent and unconventional image of a woman, but this image is associated with evil, so I cannot identify with that. I believe that witches were invented by men who needed to control women, and chose to expel those rebellious women who "endangered" the man's dominance to the margins of their societies. Regardless of whether those women were/are feminists or not, the very act of condemning them is an anti-feminist act, while expelling, or worse, prosecuting and executing them was pure evil.

Esther Naor, Untitled 9, 2016, dye sublimation on Chromaluxe metal panel

Esther Naor, How Far Would You Run with a Piece of Lead in Your Heart