by Raqi Syed

May 15, 2015

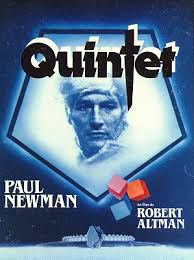

If winter did indeed come, and all the Five Kingdoms exhausted their power by killing each other and succumbing to a cold front that never left, you’d end up with a barren post global-cooling world in which the lords and ladies of House Lannister were reduced to playing some pitiful board game that is really a metaphor for the art of war and the existential dread of living. And that’s the gist of Robert Altman’s 1979 post-apocalyptic dystopian sci-fi film, Quintet.

If winter did indeed come, and all the Five Kingdoms exhausted their power by killing each other and succumbing to a cold front that never left, you’d end up with a barren post global-cooling world in which the lords and ladies of House Lannister were reduced to playing some pitiful board game that is really a metaphor for the art of war and the existential dread of living. And that’s the gist of Robert Altman’s 1979 post-apocalyptic dystopian sci-fi film, Quintet.

Set during some future ice age, Quintet follows a seal hunter named Essex (Paul Newman), and his pregnant wife Vivia (Brigitte Fossey), as they make their way to a northern city after all life has died off in the south. When they arrive at what was once a thriving city center, they discover very few people are left. Those who live, spend their days obsessively playing a board game called “Quintet.” Throughout the city, dead bodies are strewn about and are devoured by packs of man-eating dogs.

A film like this may be best watched late at night so the changeover to sleep and nightmare is seamless. Like many dystopian films, Quintet is visually arresting. The slow pacing is at times hypnotic, and at other times the quiet dread is punctuated by a relentlessly dissonant soundtrack. The edges of the frame are frosted over by what we assume to be sub-zero temperatures–a conceit that is interesting, if at times tiresome, because along with the beautiful cashmere robes these supposedly impoverished nomads wear, the frosted lens draws our attention to the constructedness of this world. It’s a little too pure and minimal and beautiful. Still, it is this perfection, set against the brutality of the hungry dogs and ruthless humans, that keeps the whole enterprise afloat. It is the mood and the dread that draw us forward.

Along with Dawn of the Dead, Quintet was one of the first films to recognize the growing significance of the American mall, not just as the center of suburban cultural life, but also the origin of our existential dread. It is suggested that the city with its many sectors may once have been a hotel. But its defunct directories, escalators, and post-modern architecture sharply signal the visual landscape of consumerism.

Paul Newman strikes me as a George Clooney prototype—he’s best when he’s playing himself—which is a lovable attractive rogue. Even his period films such as Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, feel largely contemporary, and they work because he plays a plain speaking amiable fellow, the kind of fellow you might run into anywhere in the American West. In some far flung future populated only by killers in venetian knit caps, he seems out of place. As much as I enjoy watching him in anything, I didn’t buy him in this role.

In 1979, Quintet was not well received. Even now, few have reevaluated it. It was and continues to be an uncompromisingly bleak vision of the future. It is no surprise that while it has never gained any real cult status or been remade, its visual style has been actively pilfered by all variety of dystopian films. Most recently, its minimalist snowscapes with buried trains and bodies frozen in terrifying poses, were seen in Snowpiercer. But its style and sensibility can be traced across everything from Running Man to Children of Men to Hunger Games.

Not only does the film offer no hope for the few humans still left on earth, it goes even further. Quintet is a religious belief system in which the game itself is just an intermediary between the void before birth and the void after death. Human existence is nothingness punctuated by a short lifetime of war-making. In this regard, the film is very much a product of the post Vietnam mood of disillusion, the threat of Cold War nuclear annihilation, and after decades of economic growth—a stalled economy. It is not surprising that the American public did not want to be entertained by the dismal reality of this new world. And of course it is also not unusual, that as the film once again feels eerily relevant, its message, or rather statement of truth, is still being ignored.

From Russia, With Love A review of SCREENS: A Project About “Community”

The Inner Strength of Joan Didion

Basquiat—The Unanswerable Answer to the Art World

Let’s talk about the hard stuff: Get Out

May It Last: A Portrait of the Avett Brothers

Move Over Hogwarts—The Practical Magic Is at Headfort

The Dog Days of Summer—Two Ways to Beat the Heat

The Mistress, the Publisher, His Son & His Mother

Santoalla-- the Spaces Between

Reading Arthur Miller in Tehran, The Salesman

Killing the ISIS Propaganda Machine, City of Ghosts

Bewitched, Bothered and Beguiled, The Beguiled– A Film Review

A Spoonful of Sugar-- Not Saccharine The Big Sick: A Film Review

Fiona and the Tramp, Lost in Paris- a review

Movie Review: Beatriz at Dinner

Cameraperson, dir. Kristen Johnson: stories from behind the camera lens

SELFISH, Review by Heather Zises

Winter on Fire: Ukraine’s Fight For Freedom, dir. Evgeniy Afineevsky

Strange Days directed by Kathryn Bigelow (1995)

World of Tomorrow and the Quit-Bang Language of the Future

3 Women, Directed by Robert Altman, 1977

Classic Movie Short Review: Croupier (1998)