May 12, 2017

POETRY INTERVIEW WITH CHEN CHEN

Interview by Jennifer Parker

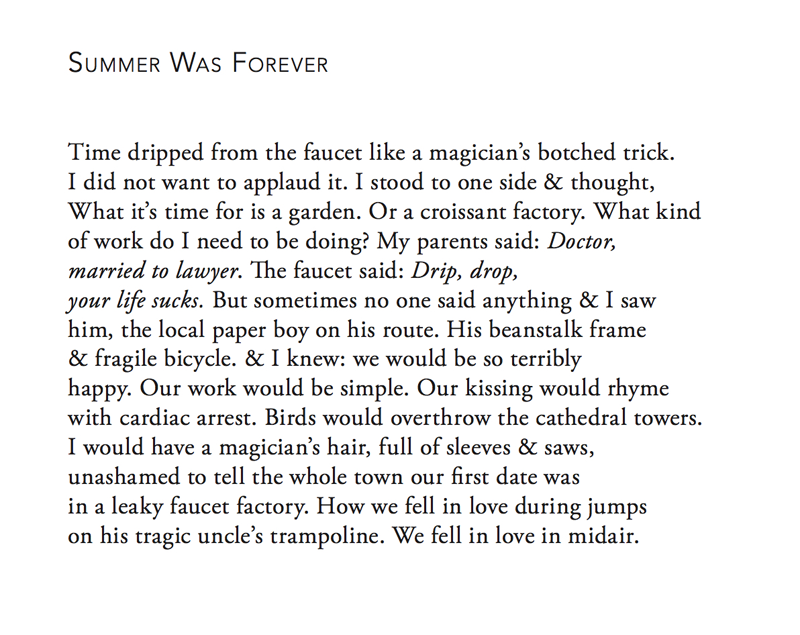

Chen Chen’s, When I Grow Up I Want to Be a List of Further Possibilities should come with a warning label: Rated M for Millennial. Chen’s debut book of poetry will make you experience an emotional range that belies his age. One feeling might be envy when you learn that Mr. Chen is a 28–year–old PhD student at Texas Tech University. Joy of what it’s like to fall in love for the first time, “How we fell in love during jumps on his tragic uncle’s trampoline. We fell in love in midair.” Frustration at what it is like to be misunderstood by your parents. “Spring says I told my mother she was living in a dream, could never go back to the way things were.” Of course, these are not feelings and experiences exclusive to Millennials. Is Chen Chen's poetry only for the generation that eschews labels? I would argue his perspective speaks to anyone who loves poetry –– from still undefined Gen–Xers to their Baby Boomer predecessors. To these demographics, I say, hang in there. It is worth it. Chen Chen may not feel grown up but he is already a list of further possibilities.

Chen Chen, Photo by Jess Chen

INTERVIEWER

What do you see as the gestalt of your poetry? Is there an overarching theme?

CHEN CHEN

Well, there are the usual poet/human obsessions with love and death. I write a lot about family. And about being a queer immigrant kid. Lately, I have realized that I am much more of a place-based writer than I thought I was. Maybe this concern with place is obvious to any reader of my work. I use quite a few place names, after all. In this book, there are mentions of and movements in: Amherst, Boston, Fort Worth, New York City, Paris, Syracuse, and probably a couple other places that I can’t recall right now.

Place: a particular tangle of weathers, tempos, denizens, temperaments, windows, demons, and shoes. Footprints. Things that fall from trees. Things that fall from the sky, through trees, onto our walking. So now I am walking into my next collection, more conscious of how place affects me, enters my language(s).

INTERVIEWER

From Bjork to The Kinks to Beyoncé, the musical influences on your poetry is certainly eclectic. Talk to me about these influences.

CHEN CHEN

I often fantasize about being a global pop sensation or the singer/front man of a very successful rock band. The only thing is, I can’t sing. I think I’m a decent dancer. I’ve said in other places (including a poem) that my favorite genre of music is deeply sad music you can dance to. In other words, depressing lyrics set to a beat or sung in an upbeat melody. I’m not sure if Beyoncé and The Kinks quite fit with that genre, but Bjork certainly does. Robyn and St. Vincent also come to mind. I like the tension between sorrow and delight, woe and fun.

But your prompt was about eclecticism. Yes, my overall tastes/influences in music run the gamut. It just doesn’t seem very real to me, to like only one type of music, to write only one type of poem. I mean, you’re going to have your obsessions and aesthetic leanings, the subjects and approaches you (subconsciously, helplessly) return to over and over. If you want to grow as a writer, though, you need to keep tapping into new sources of literary sustenance. New does not have to mean work that is current; it can just mean new to you. Sometimes new to you means an influence you haven’t returned to in a while. I keep thinking about how I need to reread Haruki Murakami’s Kafka on the Shore, for example. And to re–explore Beyoncé’s early solo albums.

INTERVIEWER

I’m particularly curious about Second Thoughts on a Winter Afternoon. You seem to have a playfulness with the language of the old and the young and the ephemeral nature of “terms of endearments."

CHEN CHEN

This poem started out of a stray thought or observation. A lot of my poems start that way. Just a thought or observation or image or sound that won’t let me go, however small and strange. In this case, I kept coming back to how odd it was that words like sick and ill could also mean, in vernacular use, cool or awesome.

And then, of course, cool and awesome also mean other things; on a literal level, cool refers to a low temperature, but not quite cold, while awesome can refer, in a more formal as well as literal context, to something that inspires an overwhelming sense of awe, which includes a sense of terror. Funny, how a cool pair of shoes can be awesome and the destructive power of a volcano can be awesome, but in no way cool. Strange and sad, how sick can be a good thing, but also the worst thing. Bewildering, how words can age, too—change their meanings, or fall out of the language altogether.

So, I am exploring, in this poem, mortality and yes, the ephemeral nature of the language we have for love, the short amount of time we have, ultimately, for loving each other, while we are all still here, still capable of using language.

Just a couple years ago, my partner’s mother was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. Though the doctors caught it at an early stage, pancreatic cancer is particularly aggressive. The doctors made this clear at the time of diagnosis. And at the same time, my own mother was facing some serious health issues. And so, all at once, everything changed, everything fell out—the ground, the words, the seeming permanence of mothers and meanings. My partner’s mother passed away in the fall of 2015. My mother is still alive, though language, warm language, is often difficult between us.

But these sentences are starting to feel too definitive, somewhat reductive—like I am explaining (away) lives and relationships and losses, when these things are ultimately unexplainable. I have in mind (again) Fanny Howe’s piece “Bewilderment,” which argues beautifully in favor of weird simultaneity, multiplicity, wild “error, errancy.” Howe is discussing both poetry and fiction. It seems to me that any fully alive writing dislikes explanation and prefers, however frightening and destabilizing (and spilling over with awe), bewilderment.

From When I Grow Up I Want to Be a List of Further Possibilities by Chen Chen

2017 BAO Editions, Ltd. Reprinted with permission.

INTERVIEWER

Besides music, what inspires you?

CHEN CHEN

Visual art—by Carrie Mae Weems, Paul Klee, Ann Hamilton, Sarah Sze, Rene Magritte, Ben McNutt, Steven Beckly, Agnes Martin, and so many others. Magritte made a gorgeous, haunting piece in 1948 called “The Lost Jockey,” which led to the lines “Has the lost jockey returned? I think / I can hear him, racing between // the lung-shaped trees” in my poem “Antarctica.”

Other sources of inspiration: the YouTube videos of Natalie Tran (a.k.a. communitychannel), who is Australian and of Vietnamese descent and hilarious and just incredibly talented. The styles and personalities of style icons like Alexa Chung and Leandra Medine (who runs the super smart, super fun fashion site Man Repeller).

INTERVIEWER

How many poetry books do you own?

CHEN CHEN

Too many. And not enough. Moving out of my apartment is going to be a massive pain.

INTERVIEWER

Do you read electronically?

CHEN CHEN

Yes. For a while, I got really into reading books on my iPad. Amazing, to store this much text in so slender a device! But I’ve stopped doing that. I can still read articles, including long ones, on an electronic device, but I prefer reading books in tangible, pages–bound–and–sitting–in–my-hand form. Maybe it’s because so much of my life already happens online. And I love online spaces and resources. I used to love email, even, back when I only received like two emails a week. My eyes crave a break from all the screens. Writing longhand gives me a break, too. A relief and a deep pleasure, to return to paper, pen, my terrible handwriting.

INTERVIEWER

What do you want to see more of in contemporary poetry?

CHEN CHEN

More emotional range within collections and also within individual poems. I love work that embraces highs and lows and middles and unders and tucked away in the corners. I don’t think anyone feels exactly the same way all the time. It’s exhilarating and closer to the truth when a poem swerves and shifts emotional gears. If a poem seems to lean heavily into a single emotion, I get suspicious. Why this one emotion? A poem can feel manipulative, pushing the reader into a tight space and demanding that the reader stay there, feel only that.

Then again, there are poems I love that manage to do a lot with very little. My own expansive, maximalist tendencies are coming out here. Not that poem length necessarily determines poem scope. A tiny poem can roam all over the place, while a big poem can stay put, maintaining an intense focus.

Still, it bothers me when it seems like a writer has decided that a particular acre of say, melancholy, is his or her territory and that’s it. I’d rather follow Pablo Neruda’s example: write about socks and write about the Spanish Civil War, bring in both “lilies and urine.” Be impure. Or as Ms. Frizzle from The Magic School Bus says, “Take chances, make mistakes, get messy!” I’m interested in a restless poetry that takes me beyond and beneath and between what I think I’m feeling, what I think I can say.

Chen Chen - When I Grow Up

I Want To Be

A List Of Further Possibilities

INTERVIEWER

Several of your poems address your emotional pain with your mother her treating your sexuality as an affliction. Have you always found poetry a means of expressing grief and disappointment?

CHEN CHEN

It is true that one reason I started writing poetry was because I felt like I couldn’t say, just in everyday conversation with my family, what I was feeling when it came to my sexuality. I felt like it was impossible to say certain things even to myself. Poetry was a way into language, into saying, where the usual conventions and limitations didn’t apply. To identify as queer, I had to queer my relationship to words.

Another reason I started writing poetry was because I fell in love with the music of particular poems. Poems like Dylan Thomas’s “Fern Hill,” Emily Dickinson’s “Because I could not stop for death,” Robert Hayden’s “Those Winter Sundays.” I didn’t know entirely what these poems meant, but I loved, immediately, their sound.

INTERVIEWER

At what point did you realize technically and thematically that you had a collection of work?

CHEN CHEN

I think I realized this after I wrote the poem “The Cuckoo Cry,” which is in the second section of the book. This poem again looks at the conflict between a mother, who struggles to understand, and a teenage son, who’s coming to terms with his sexuality, but is not quite ready to come out as gay. After “The Cuckoo Cry,” I knew I had a whole set of poems that examined this tension, and I started to see how this tension could be the heart of the collection. Many of the other poems engaging this subject had already been written: “Race to the Tree,” “First Light,” “How I Became Sagacious,” “Poem in Noisy Mouthfuls,” “Poplar Street.”

Actually, though, for a while I hesitated making the mother/son relationship so central to the book. I included all these other poems in the early version of my manuscript, poems that had little to do with this main subject. I was nervous about presenting such vulnerable work. Jericho Brown, who picked the book for the A. Poulin, Jr. Poetry Prize, pushed me to embrace the vulnerability, which led ultimately to a much clearer shape and arc for the collection. In other words, I cut a bunch of poems. And worked to make what remained stronger and more cohesive. It took several rounds of revision. I’m glad Jericho pushed me and I’m glad I took the time to reimagine how these poems might live together. The heart was there all along, but I had to learn to listen to its beat.

INTERVIEWER

Do you plan the structure of your poems or do they evolve? I am particularly thinking about For I Will Consider My Boyfriend Jeffrey. The poem, “For I Will Consider My Cat Geoffrey” is in the public domain. Did you start out wanting to pay homage to Christopher Smart’s poem? What spoke to you about it?

CHEN CHEN

With this poem, I had the title and the idea for it before writing any of the actual piece. Usually, for me, this preconceived idea approach spells disaster. I tend to feel stifled by having to stick to some initial premise. My writing heart wants to leap away from the planned, the scheduled route.

Somehow, though, the structure of Smart’s poem lent itself to a very playful, flexible process when I was working on my homage/imitation. Perhaps it was Smart’s use of anaphora and the list form. I was already writing my own poems that used a great deal of anaphora and the list form. The title of my book, after all, has the word list in it. So, I felt at home in Smart’s structure, which felt roomy, full of space for unplanned digression and unscheduled circling back.

I love how obsessively and carefully Smart’s poem describes his cat. I love how the poem swerves from philosophical to quotidian to religious to complete immersion in the specifically feline. I wanted to write a poem that touched upon a similar range of concerns. And I wanted to write a love poem for Jeff.

INTERVIEWER

Lastly, who is your favorite Asian American woman poet?

CHEN CHEN

I don’t like saying favorite. Too final and like “this is the one representative of an entire group!” Nah. Instead, let me recommend some more poets I’ve been reading or rereading lately.

Solmaz Sharif. Her debut Look (Copper Canyon Press, 2016) is !!!!!

Michelle Lin. Her debut A House Made of Water (Sibling Rivalry Press, 2017) is <33333

Bhanu Kapil. Her book Schizophrene (Nightboat Books, 2011) is an emoji yet to be invented. And her book The Vertical Interrogation of Strangers (Kelsey Street Press, 2001) is a major influence on my new manuscript.

Too, keep an eye out for Aimee Nezhukumatathil’s next book, Oceanic (Copper Canyon Press, early 2018), and my pressmate Christine Kitano’s next book, Sky Country (BOA Editions, fall 2017)